If you want the 50-cent tour of South Dakota’s Badlands and surroundings, do it yourself by hanging a left at Wall Drug, spending a few hours off I-90, and be on your way in time for dinner in Rapid City.

Or, you can hire someone like Warren “Guss” Yellowhair, Lakota artist, teacher, linguist and tour guide, to take you on a trip into the real prairie that lies beyond the national park, into the historic reservation of Pine Ridge.

Have him stand at the grave where the Lakotas massacred at Wounded Knee, within the reservation, lie, and sing a remorseful song to the dead. Have him show you his art, from willow dream keepers, to ledger book art prints of war chief Crazy Horse.

And, while he drives amidst the abject poverty of the villages within this huge prairie reservation, have him tell a joke or two while explaining that he feels the Lakota here are in the beginnings of lifting themselves out of all this by the best means possible: through education, self-respect, and a return to the “old ways,” that have been lost for more than 100 years.

We drove off towards “the res,” as Guss puts it (his Lakota name, by the way, isn’t Guss; it’s Tasunkanajin, or His Horse Is Standing), as he explained that he’s been a traditional Lakota artist for 25 years now, learning brain tanning buffalo hides from his uncle, other artists, and elders, while also about making drums robes, and unique ledger book art. That art form began in the 1870s, he said.

“It’s a combination of two cultures. Trading posts used paper, ink and pen to keep track of inventory and records on ledger books, and for the first time, Lakota turned from hides to art on that same paper, creating pictographs telling the history of the culture, and it’s given me the opportunity to travel within the U.S. and to Germany four times.”

Guss also creates parfleche art, rawhide boxes originally created to hold items, and used in arrow shields. He is an instructor at Oglala Lakota College, teaching students on the Pine Ridge reservation art, Lakota language immersion and self-respect. The latter, through what he calls winter, fall, summer and spring camps for reservation youth that take place each year. The college has conferred more than 3,000 degrees in everything from nursing to teaching.

As he drove us through the Dakota plains and in and out of the Badlands, he told us about the reservation, 100 miles long, 50 wide, where more than 30,000 Lakota live, or rather, exist. Lakota, he says, translates to friends, or allies. “We’re very friendly but if you poke us in the wrong way...,” he joked, with more than a hint of historical reference. The word Sioux came from a mix of French and Ojibway, so most Lakota don’t like that word.

On the day of the Lakota new year, the last day of April (interestingly, the same weekend we fly fishermen celebrate the opening of trout season in Michigan), we go to Thunderbird Mountain and offer tobacco and prayers to welcome back the thunder beings. We also go to Old Baldy and Harney Peak in the Black Hills.” Wind Cave also is sacred because the Lakota believe that is where they emerged onto the earth.

But on nine college centers, some 1,500 students per semester are working towards four-year degrees, to lift up the population from poverty as part of the Proud Horse Institute.

“We do have a casino, called Prairie Winds. It provides some jobs. In a place where there is 60 to 70 percent unemployment every little bit helps.”

As he related that story, we stopped at Scenic, a small near-ghost town on the edge of the Badlands, which saw its last visitor decades ago. Owned by one person, it was rumored it’d been just sold to the Hell’s Angels. One of its few residents greeted us, then asked for a handout.

It was an example of what Guss was just talking about.

Visitors who want to immerse themselves in the reservation can stay at several properties, and many do, including many Europeans who can’t get enough of the West. There are two hotels, one at the Prairie Winds Casino and the other, Lakota Prairie Ranch. There are also bed & breakfasts, but the real draws are also tragic ones.

Wounded Knee

The upside down American Flag, flown at a house near the small cemetery looking over Wounded Knee Creek tells all you need to know about what happened here during one of the most shameful events in U.S. military history.

We walked up the knoll overlooking the “battlefield,” in quotes because it wasn’t a battle at all.

In frigid December 1890, the Lakota chief Big Foot, suffering from pneumonia, had moved his band here after fearing he would be the next target after Sitting Bull was killed, and he was afraid to seek refuge with Red Cloud in Pine Ridge.

Red Cloud, who does not have a great reputation among many Lakota, did not protect Big Foot. So as the Army met with Big Foot, to give up their arms. A deaf Indian was asked to give up his rifle. Since he couldn’t hear, two soldiers held him, and his rifle discharged in the scuffle, according to some reports. That was all it took. Soon, the wrath of the re-formed 7th Cavalry, some say to revenge the victory at Little Big Horn, fell upon the encampment along the creek. More than 300 of Big Foot’s band lay dead along the creek, including Big Foot, a majority women and children.

After a three-day blizzard, the Indian dead were buried at the top of a hill in a mass grave overlooking the site, and from which deadly rapid-fire artillery rained down upon Big Foot and the soldiers below. And the government handed out 20—20—of Medals of Honor after the massacre to the participants. Twenty-five Army died, many believed to be victims of friendly fire.

As we visited the grave, Guss sang his moving song. The words, he explained, meant this: Great Spirit, you’re the only one with great compassion; Through your compassion I am strong; Because of the sins of the world, I am having a hard time.

“I had though that was an appropriate song, calling upon the Creator for strength to continue as a nation of people regardless of what was done to us,” he said later. “The genocide here was the pinnacle of the breaking of the sacred hoop of life for our nation.”

The site was a turning point in 1973, when Russell Means and other American Indian Movement leaders made their stand for 77 days at a church where Big Foot and his band are buried, to call attention to the reservation’s dismal poverty, and to begin what Guss and others are doing today—through the old ways and education, to provide hope, and most of all, pride, in being Lakota.

“The government fulfills the treaty obligations by handing out mediocre services, and that creates two states of mind here, that if you’re given something, why should I work, or the government owes me. So a lot of factors went into creating this situation,” he says.

“But we’ve got the land, resources and the people, but because of that mindset it’s hard. We have the largest dropout rate in the U.S. here. People begin to loose that dream and get caught up in drugs and that puts more dirt on the grave,” Guss adds. “I like to say that the people here can be perfectly happy to be living miserably comfortable.”

But there are signs of change. “With our college, people are beginning to educate themselves, so I do see a future for our young people. Our old style of government was families coming to help each other, and people are going back to that. That gives power back to they people so they can do some of these things on their own. For the longest time we were made to feel ashamed of our history and to speak the language.

“All this ties into being proud of being Lakota,” he says.

Guss says that besides tours like the one we were on, you can also book pheasant or buffalo hunts and other outdoor pursuits either through the Pine Ridge Area Chamber of Commerce, home of a small but good museum, and the Oglala Sioux Parks and Recreation Authority at

www.osprabuffalokeepers.com.

A stop by the Red Cloud School, near the town of Pine Ridge where another good museum is located, along with a shop selling lots of Lakota-made art, also is worthwhile.

And, you can stay on the reservation and learn how the Lakota are trying to escape from 100-plus years of well-meaning, but misguided, government action, and self-hatred.

When You Go

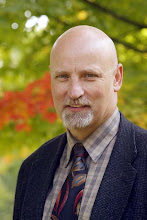

A self-taught traditional artist, Warren “Guss” Yellowhair also has an AA in Lakota Studies from Oglala Lakota College, and teaches there. He has displayed his art in many shows and exhibitions, including Gold Rush Days in Sidney, NE, and the Coeur d'Alene Art Show in Idaho, and elsewhere across the country.

He also helped organize portrayals during the Lewis & Clark bicentennial sponsored by the National Park Service with the Lakota Heritage Society. His art is available and many local powwows and in stores such as Prairie Edge Gallery in Rapid City and Lakota Prairie Ranch Resort, near Kyle, and on eBay. For tour information, go to

www.nativediscovery.org. To contact Guss about both his art and tours, call 605-454-0507. Or email him at

Tasunkanajin_1@yahoo.com.

For a list of upcoming powwows on Pine Ridge, along with other guides and native artists, go to the native discovery.org site, or

www.pineridgechamber.com. The site also has information on reservation accommodations including campgrounds, hotels, and bed & breakfasts, plus horseback riding, fishing and other cultural events and art galleries and attractions, from the Oglala Lakota College History Center in Kyle, to area guest ranches.

While you’re there, buy a Tanka Bar, a natural buffalo and cranberry energy bar made on the reservation. Learn more at

www.tankabar.com.

|

| Warren Guss Yellohair displays some of his Lakota art |

|

| A monument to the dead from Wounded Knee stands over the cemetery as prayer offerings flutter in the wind |